By Mike Barajas

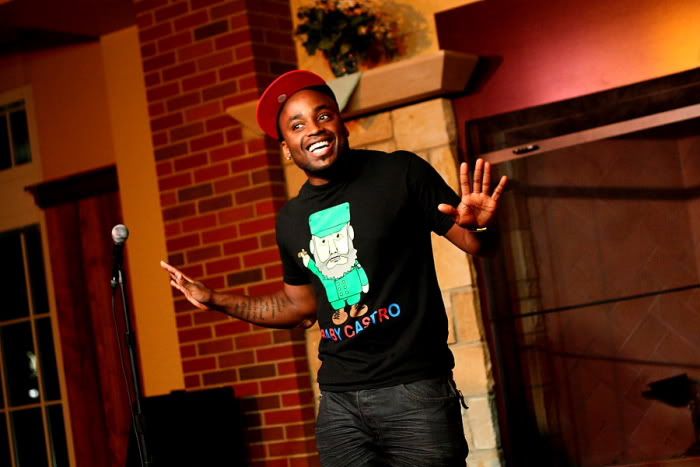

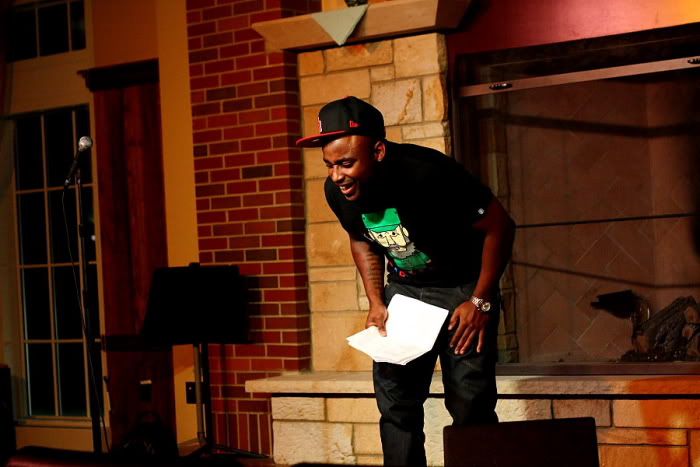

Javon Johnson says he strives to make himself vulnerable while on stage, vulnerable in a way that black men, even poets, rarely show. In his shows, Johnson, a national poetry slam champion, strives to present a humorous, deep and multi-faceted view of race and masculinity.

Johnson, born and raised in South Central L.A., has performed on HBO’s “Def Poetry Jam” and BET’s “Lyric Café,” and gives readings all over the country. Before his show Saturday night at the Front Room, I sat down and talked to Johnson about his work. Here are some excerpts from the interview:

What drew you to poetry and spoken word?

JJ: The narrative that I always tell people, and it’s a very true story, is that I started like I think most young boys start out doing this prior to “Def Poetry Jam,” which is a young girl said, “I heard you write poetry,” and my answer was, “Uh, yeah I do. Do you want a poem?” And that was the first poem I ever wrote. It was just to talk to girls at first; they think you’re deep when you write a poem. That was initially the start of it, in high school. What kept me going in it was I had read a book called “Burning Down the House”; it was the 1998 Nuyorican slam team. The members, which I think are most important, were Roger Bonair-Agard, their coach, Guy LeCharles Gonzales, Alix Olson and Lynn Procope. And I was like, “This stuff is amazing!” I was like, “Holy shit” and then I wanted to find more stuff with this so-called slam poetry. I ended up watching the movie “Slam” with Saul Williams and Sonja Sohn… and I ended up watching a documentary called “Slam Nation”… And then when I started writing it myself and started performing, I went to a spot called 33 1/3 in Silver Lake, which is sort of a gentrified area of Los Angeles.

What do you get out of spoken word and poetry?

JJ: I think, you know, you’ll hear from a bunch of poets, you know, “it’s moving, it’s makes me empathic, I understand, I’m connected and communicating with people,” and I don’t want to get away from any of that. I think all of the meaningful communicative aspects of it are beautiful and brilliant. But I think what we all forget to say sometimes is that it’s just fun. It’s just flat-out fun up there. And I’m funny at times in some of my poems, and I like to have that fun on stage. It’s fun for me to perform and read what I write and share what it is that I wrote. But, all of those other things too, that it is meaningful, that there’s nothing quite like the comment of somebody coming up to you going, “Hey, you have no idea how much I needed to hear that poem,” or “You don’t know what that poem did for me.” You know what I mean? Those kinds of comments, all of that stuff.

What inspires your poetry?

JJ: A lot of different things, you name it. Everyday life, mostly things that happen to me. I write real stories, like I don’t really make up a lot of stuff. Most of the stuff I write about is extremely real. If you ever hear me say, “He said,” or “She said,” that stuff happened for real. And that’s recent, and that’s partially sparked by Shihan, a very well known poet from “Def Poetry Jam”… One of the things he inspired me to do is write more personally, to just really tell my story. Because prior to that, I didn’t really share much, and there’s a remarkable difference between what I used to write when I started out and what I write now. And part of that is growth; you should always look back at your work and do something different.

What do you want people to take away from what you write?

JJ: There’s always stuff behind my poems that I think I want people to get, but I understand that people will take from whatever it is that I write whatever they need. People aren’t empty vessels waiting to be fed. We come to these engagements with all of our baggage and cultural capital. And we pick and choose what it is that we need, and we decipher things how it is that we need them. This is how people can engage in the same exact event and see entirely two different things.

But a lot of my stuff, for me at least, has a deeper meaning behind it, even the funny stuff. Like, for example, I have a poem called “The Black Poem” and it was written after I went to a poetry venue on the south side of Chicago, which is a very black part of town. But one of the things was a lot of these people were reading these stereotypically black poems. They were defining blackness so narrowly that no one gets to be black. And for me, I wrote that poem, which is absurd and it just goes off about how black the poem is – it’s somewhere between 11:59 and 12-midnight black, you know? It’s genetically predisposed to the kind of athleticism that would give you more airtime than Michael Jordan black. You know? These kinds of things, and [the poem’s] humorous, and it goes on. And the key part of that poem for me is that when we write those kinds of poems seriously, I think we often define blackness so narrowly that not only white people can’t hear me, no one else can either, and so obviously no one gets to be black. That’s initially what that poem’s supposed to be about. So I try to engage in critiques that I would engage in on an academic level, so to speak. I try to critique, but I just do so in poetry.

You inject social and political critique into your poetry?

JJ: The simple and skinny answer is yeah; I mean, there’s a lot of race critiques, there’s gender critiques about gender inequity, there’s class stuff in other poems. It just really depends on the mood. Sometimes I write about love; sometimes I write about politics straight up. I like to think now that I always write about love, because even if it’s not a love poem per se, and even if it’s a political rant, I’m writing it out of a place of love for somebody or for something. So now, I like to think that I always write love poems.

I tackle things in different ways, through different kinds of poems. It’s just a matter of what I’m feeling at the time. I just wrote a poem about gender issues with men, and their inabilities to engage themselves emotionally on a proper level. You know, all those kinds of things.

I think the biggest thing that I do is I am vulnerable on stage in ways that were never prepared for black men to be vulnerable. What we expect from a black male poet is someone who’s yelling, someone who’s frustrated with “the system” and “the man.” And while that stuff is valid on many levels, and I’m not downplaying that at all, what we don’t expect is for black men say is, “I hurt too.” What we don’t expect for a black man who’s heterosexual is to say, “Yes, I love my other black men, I want them to be well.” We don’t expect men to say, even in some liberal spaces, is that men need to get their shit together and stop doing XYZ and perpetuating patriarchal practices. We don’t expect that kind of vulnerability. We don’t expect men to cry on stage, like that’s not “manly.” And I personally think men, and especially black men in a different way, have an unhealthy preoccupation with what constitutes “manly.”

No comments:

Post a Comment